Wired recently published an article on dark retreats, and I think it unintentionally raises some really good questions about spiritual endeavors and practice. For those of you who have done or contemplate undertaking a dark retreat, it’s a good and pretty short read.

I’ve gone into the dark twice. Once for six days and once for the traditional 49 days. I hope to do another retreat for two weeks later this year. With the right preparation, practice and training, they are among the most transformative experiences (or non-experiences) one can have. Dark retreats don’t serve a single purpose. They can be used for deep rest and relaxation. They can bring physical, mental and emotional healing. They can bring on ordinary visions (which are cool but don’t really serve any purpose), nightmarish visions (samsaric visions par excellence), or the clear light visions that arise and fade when stably resting in the nature of mind (a Dzogchen practice).

What the article got me to thinking about, however, isn’t dark retreats (I’ll come back to those in another blog). What it did spark is reflection on why we practice. Or, at least, why I started to practice, and why I continue now, some twenty years later. There are so many reasons to engage in spiritual activity, but they can really be divided into two categories: Practice to glorify the egoic self, and practice to pacify the egoic self.

The title of the Wired article gets right into the heart of how not to practice. Spiritual conquest takes one down a dark and lonely path. (Funnily enough, this is the opposite of what a successful dark retreat will do, which reveals in inextinguishable clear light of awareness that illuminates all.) Another name for the ego is, to quote Tenzin Wangyal Rinpoche, a pain body. My ordinary ego is an aggregation of my identities, which are in turn calcifications of my anger, attachment and ignorance, along with all my hurts, pride, fears and more. Ego is a reification that seeks to become harder and harder, more and more real to itself and validated by others. When I am moved by my ego/pain body as opposed to being responsive to it, feeding it with experiences and praise, the less present my true self manifests in the world. As my ego gets bigger the scope of my inner life gets smaller.

History and literature are full of examples of all the ways that moving from the ego goes awry. Anatole France’s Thais is a brilliant tale of the the corrosive power of ego to soul. Jekyll and Hyde, another, as is The Picture of Dorian Gray. Members of the clergy who abuse their power and perceived spirituality for personal gain and power and the sex scandals that have hit so many spiritual organizations - Buddhist, Christian and otherwise - are examples of such superficiality. The appearance of being spiritual bears no correlation to the shape and color of one’s soul/self. If we are driven by our ego and our untamed desires, something turning out well is at best only an accident (or, perhaps, the grace of God(s)).

In opposition to this is practice informed by seeing and responding to our pain bodies: the ways in which the ego keeps piling injury upon injury, hardening our hearts and deadening our spirits. It’s like the classic saying in 12-step programs: “All my best ideas landed me addicted, at the end of my rope, sitting in a church basement surrounded by other addicts.” When we see the ways in which we are disconnected from our families, from ourselves, chasing things whose happiness is at best ephemeral, chasing ideas and desires and often ending up with the opposite of what we truly want, unintentionally harming ourselves and others: then we are ready to come onto the path of meaningful spiritual practice. It’s only when we see the truth of suffering (our own and others) that we can really “progress,” such as it is.

So then, we see how “things are rotten in the state of Denmark” - Denmark being code for all the ways in which we have deadened our existence, reduced ourselves from our mature as grand, miraculous beings of light, wisdom, and love into small, defensive, and lonely little hungry ghosts (maybe it’s only me?). We resolve that something must change. Often we come to a practice or to faith feeling that we are more than wounded; that we are broken and unworthy and in need of redemption. We may feel shame over our past, over who we think we are and who we have been. But at the heart of these feelings is the real knowledge that we are capable of so much more - that we are entitled to know and feel and express love and joy, and to be wise and good in our hearts and minds.

So, in both cases we are driven by the need to accomplish. In the case of “Spiritual Conquest”, per the Wired article, it is an accomplishment perceived by others. For the diligent practitioner, it is the need to accomplish a change in our relationships to ourselves and the world around us. Practice is always about learning to open our hearts and minds, never to close or harden them. These transformation are often subtle, and there are rarely any obvious, outward visible signs. There’s nothing to post on social media. There’s no T-shirt showing you were at the right event or retreat. There is just you living your life with more freedom and space, more compassion and wisdom.

Whether chasing experiences or working toward self transformation, the idea of who we are drives us. But in the former, the motivation is self-aggrandizement, further reification and mere appearance; and in the latter it’s pacification of the ego. When we recognize, face, and embrace the wounds we carry, we discover that practice is a balm for the soul. It restores us to our true self, something we may have never encountered before but always knew was there.

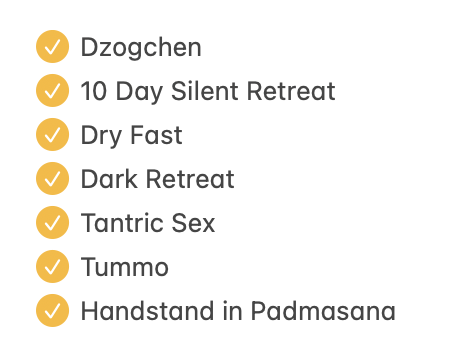

There is a tendency to want to be the superior practitioner: no one seeks to be average, or, worse, below average. We want to sit the longest, be the most still, attend the “highest” teachings with the “best” teachers. We want to conquer the hardest poses in a yoga class and undertake demanding practices. We want visions of angels and dakinis and buddhafields. We want other’s to admire us for what we’ve accomplished or done. Chögyam Trungpa called this “spiritual materialism,” and it’s a great expression to capture what’s going on within. Spirituality becomes just one more thing to master, possess or own. In our culture we learn from an early age that we should strive to be the best, the one at the top and who gets recognized. When we practice like this there is really never any good result. In fact, the spiritual checklist approach is a movement away from what we find in authentically motivated spirituality. In the grip of the untamed ego we humans generally and consistently do the opposite of what we want. Our desire to possess a result is often the very reason we cannot achieve our aims (there is so much more to say about this)! Like in the book Thais, we mistake the fragile veneer of a spiritual life for the depth and solidity of our soul. They are not the same!

The other risk here is that we dive in to practices or experiences when we aren’t ready. In the case of the Wired article, the individual who fled in terror after 12 hours in a dark retreat clearly had no preparation. Spiritual practices are not, generally, dangerous, though they can be when we are ill prepared for them. The path is in most cases is a gradual one. Learn to sit for 5 minutes before you sit in for 3 hours. Learn to breath well before you try tummo. Many languages have expressions to the effect of “Slowly, slowly.” “Poco y poco”, in Spanish. “Ka le ka le” in Tibetan. Coming to our practice with pride, arrogance, a sense of entitlement, etc. is a pretty surefire way to assure bad results. In the case of a dark retreat, we must be prepared to encounter the whole of our mind - not only what we know is in it, but what lies in it’s shadows. If we have things we are not ready to see, they may still well come out in the dark. One isn’t given the choice to see what comes up. This means, one needs tools to work with what arises, and the openess to meet it with lovingkindness. On the other hand, if we dive in to a practice and we find ourselves growing disturbed in any way, stopping the practice and stepping back is always appropriate. It is very good that the fellow in the article had the wisdom not to persevere. It will be even better if he chooses to take what arose seriously and explore what underlies such terrors in the dark.

Many spiritual traditions encourage us not to talk abut our spiritual practices or accomplishments. By remaining in silence, sharing only with our teachers, or others with whom we are in deep and sacred relationship, we avoid the temptation to think ourselves special, feel pride in our practice, reify or otherwise objectify it. When we leave the fruits of our practice in silence, in the space of our hearts, then they can take root, grow and flourish. This doesn’t mean that there is never a place to share about one’s experiences. But those opportunities are pretty far and few between. There is a reason that humility is considered one of the great virtues in all traditions.

The Bhagavad Gita tells us is the best explication of how to live and to pracitice, and the ways in which one should not love or practice. In summary:

When a person gives up all selfish desires arising from the mind, O Partha,

Satisfied within the self, by the self alone, then that person is said to be established in profound knowledge.One whose mind is undisturbed in suffering, who is free from desire in all kinds of happiness,

Whose passion, fear, and all kinds of anger have departed - such a person estabklished in thought is said to be a sage.One who, everywhere, is without sentimentality upon encountering this or that, things pleasant or unpleasant,

Who neither rejoices or despises, the profound knowledge of such a person is firmly established.

Bhagavad Gita, 2, 55-57, Trans. Graham Schweig

This is the goal of practice, to be able to rest and be fully engaged in life, lively but undisturbed what what happens. That’s how, to quote Leonard Cohen, “the light gets in.” That’s what happens when we have the right motivations for our practice and our actions in this world.

Rob

Comments